When the wildfires ripped through the Pacific Palisades and Altadena in January, Michael Flood, chief executive of the L.A. Regional Food Bank, knew the demand for aid would explode.

“It was especially high in January through March as so many people were displaced and lost power and water,” Flood said. He saw demand for food relief rise 30%. “It is still high,” he said. “People had to move in with family and friends around the county. We did a food bank in Inglewood in February and we saw just how many had been displaced by both fires.”

His organization, which provides food assistance to hundreds of thousands of Angelenos every month, got significant help from the FireAid benefit concert in January. That show, produced by Clippers owner Steve Ballmer and music mogul Irving Azoff, featured dozens of A-list musicians like Olivia Rodrigo, Billie Eilish and the Red Hot Chili Peppers performing at the Kia Forum and Intuit Dome. The event — along with matching donations from Ballmer and his wife Connie — raised $100 million for wildfire relief.

Six months after the fires, The Times individually contacted over a hundred organizations that received FireAid funds, nonprofits in food aid, housing, mental health, childcare and ecological resilience. A review of the beneficiaries’ grants and work showed how FireAid was an urgent lifeline in the worst of the disaster and beyond.

“We want people to understand that there’s been a thoughtful process behind this, and our top priority was trying to do what people needed, and do what’s best for fire survivors,” said Lisa Cleri Reale, a member of FireAid’s grant advisory committee.

Yet the grant recipients are still grappling with the deep, intertwined needs of a scarred Los Angeles. That work will require investment for years to come.

“The high cost of rent, and food prices being 25% higher, it all puts pressure on people already struggling to meet basic needs,” Flood said. “Even though we’re six months from the fires, there’s still such a significant need.”

In between sets, FireAid highlighted individual stories of incalculable tragedy. One family, the Williams of Altadena, recalled onstage that “At 3:30 in the morning, the warning hit our phones. We grabbed what we could — our grandmother’s special clock, our father’s ashes, our 47-year-old parrot Hank. Among the five of us standing here, we lost four homes and we’re struggling to find places to live.”

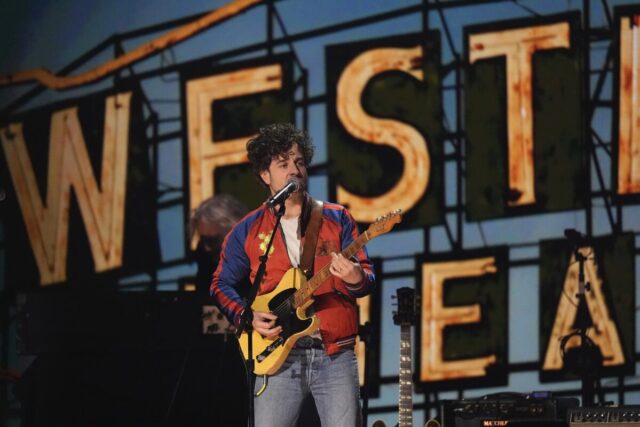

Taylor Goldsmith of Dawes performs during the FireAid benefit concert on Jan. 30 at The Forum in Inglewood, Calif.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision/Associated Press)

For music fans calling in donations during Stevie Nicks’ and Sting’s sets though, it was fair to ask how those specific groups were chosen, and how they were making a difference to families like the Williams. In late May, the Palisades Community Council sent a letter to the Annenberg Foundation and FireAid organizers. The critical letter asked for a full accounting of the grants, and clarity on the decision-making process behind them.

The FireAid organization responded with the full timeline and the grant amounts they’d dispersed, along with plans for future rounds and applications for small groups to apply.

“This is very different from other philanthropy. We have a different magnifying glass looking at us,” Reale said. “There are people who bought tickets to these concerts, who donated on the website, the musicians who gave their time, these people want to know that their contributions are doing what’s best. We have fire survivors as our top priority, but we’re also asking — can we look at the FireAid donors and explain our decisions in a tangible way?”

In breaking down the group’s grant-making process, FireAid representatives showed how its earliest priorities were organizations providing direct cash, food and shelter to survivors.

In February, $1 million went to the L.A. Regional Food Bank, followed by a second grant of $250,000. The money went to pay extra drivers, forklift operators and warehouse workers to help process and distribute donations after the fires. “We’re a year-round program, so when disaster strikes, that gets laid on top of it,” Flood said.

With its February grant, the group Inclusive Action distributed $500 cash grants to landscapers, street vendors and other outdoor workers who lost jobs or homes in the fires. The Change Reaction, a direct-aid group, got $2 million from the first round of FireAid grants.

Change Reaction’s president, Wade Trimmer, said that the funds provided 2,500 recipients with grants up to $15,000 for immediate rent and transportation needs.

The Pasadena Jewish Temple & Center burns during the Eaton fire in Pasadena, Calif., on Jan. 7.

(

Josh Edelson / AFP via Getty Images)

“The strategy was to stabilize as many households as we could because when you have stability, you make better decisions,” Trimmer said. “Even for wealthy people in the Palisades, it was still a full-time job and an absolute nightmare dealing with it all. But in Altadena, there was an older population with multigenerational households, so for every house that burned, that affected two or three households.”

That money helped sustain Elizabeth Jackson, the owner of White Lotus, a workout studio in the Palisades that employed 14 fitness instructors. Jackson lost both her home and business in the fires. “We lost every single client at the studio because our clients lost their homes,” Jackson said. “They’re all starting their lives over.”

Through a White Lotus regular, Jackson got in touch with Change Reaction, which used some of its FireAid funds to give $1,000 to each White Lotus staffer and replace fire-damaged equipment so Jackson could reopen in a smaller space nearby. She hopes to return to her old property once it is rebuilt.

“That support was a bright light in all the ugliness that happened,” she said. “It’s awful to lose the studio, but being on the receiving side of that beauty, it’s even more powerful than the negative. It keeps me going.”

The physical devastation in the burn zones was incomprehensible. For the immediate work of debris removal, flood prevention and vegetation clearing, Team Rubicon got a $250,000 grant. “FireAid demonstrated a clear understanding of the unpredictable nature of wildfire response, and they recognized the importance of flexibility and agility during both the immediate relief and long-term recovery phases,” the group’s spokesperson Thomas Brown said. “They invested in our work at a critical moment.”

Wounded and displaced pets received free veterinary care through groups like the Pasadena Humane Society and Community Animal Medicine Project. Yet many people tasked with helping others were also suffering. Many local nonprofit workers lost homes and workplaces, and needed aid to stay afloat while serving others.

“A lot of our staff were in crisis too, where they lost homes or were the only house left on their street in Altadena,” said Stacey Roth of Hillsides, a Pasadena foster care and youth mental health facility near the Eaton fire zone. One of Hillsides’ main residential buildings suffered significant smoke damage, and the FireAid grant allowed the facility to move its vulnerable population to hotels nearby.

The fire in Pacific Palisades quickly consumed more than 1,200 acres on Jan. 7, pushed by gusting Santa Ana winds.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Michael Sidman of Jewish Family Service lost his own home in the Eaton fire in Altadena. “I’m very lucky to have a strong support system, but it’s been a nightmare navigating this,” he said. “When you think about people navigating this alone with no family, and unsure how to connect with services, I don’t know what they’d do.”

His organization used its $250,000 grant from FireAid largely for comprehensive disaster case management work, particularly for survivors to manage the FEMA bureaucracy. Other early grants went to groups like Legal Aid, Bet Tzedek Legal and Public Counsel to help with insurance claims, as documents lost in the fires made proving residence and home ownership challenging.

“At first, people didn’t know where they’d spend the night, didn’t know where to get food and were all grieving for their mental health,” Sidman said. “Now we see the need shifting to long-term effects and recovery plans, providing step-by-step facilitation of how to get their lives back on track.”

As the weeks of recovery continued, FireAid’s priorities for its second $25-million grant round expanded to longer-term efforts like insurance and government case management, mental health services, navigating home rebuilding permits and environmental recovery.

“It’s one thing to get people cash aid, but it’s another to help them navigate the future,” Reale said. “Even though rebuilding seemed far away back in January, we knew that people needed to figure out their finances. Some of the fire victims our grantees were working with were on precarious ground financially even before the fires. Our job was to get them into a strong position so when they were ready to rebuild their lives, they wouldn’t be floundering.”

The fires significantly disrupted school and childcare for young families, many of whom are now homeless or miles away from family and resources.

Victor Dominguez, president and chief executive of YMCA of Metropolitan Los Angeles, said its FireAid grant provided emergency childcare for a thousand displaced children, along with mental health resources and camp activities for children to reconnect with their fire-scarred neighborhoods.

“Young kids experienced so many traumatic things in their local communities,” Dominguez said. “After the fires, kids and families had an opportunity to go somewhere safe where they trust. Now we are seeing the shock, the reality of this being a long-term experience. We were able to hire more licensed social workers, and the money we received from FireAid helped support that.”

Mental health services remained a complex and ongoing need, especially for youth and children. “I went to the Sears building a couple of months ago, where Pali High is temporally housed, to look at this big wall where kids had posted notes about how they felt post-fires,” Reale said. “You could see that the trauma is still alive and well. Nobody’s healing overnight.”

Much of the aid dispersed was less visible to the public, if lifesaving for its recipients. Yet two marquee FireAid projects involved rebuilding and revamping damaged public green space, including Loma Alta Park, near Altadena. A second site, Palisades Park, will open this summer.

Alana Lewis, who was impacted by the recent Eaton Canyon wildfires, at a community gathering at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in Altadena on Jan. 17.

(James Carbone/For De Los)

As residents in the burned areas explore rebuilding homes, issues like soil testing, remediation and permitting have emerged as new bureaucratic challenges for future FireAid grants to help navigate.

Questions around how to support rebuilding — or where it should happen at all — are complex. FireAid’s third round of grants are likely to focus on longer-term mitigation efforts and environmental resilience to prevent and manage future fires, which are all but inevitable in climate change.

“The reality is we don’t have enough money to rebuild every lot that was lost,” Reale said. “What we can do is wrap ourselves around tools or ways that a lot of people can benefit from when they’re ready to rebuild, and that could be the sustainable models. We can’t rebuild the same way. So we’ll put our money toward things that are helping people with home hardening models, and things to prevent and mitigate future fires.”

For the more intangible cultural communities lost — like the music studios, rehearsal rooms and artists’ homes burned in both fires — recovery will be diffuse. The January concert made FireAid a natural fit as a partner for MusiCares, the Recording Academy’s affiliated charity. That organization declined to say how much FireAid gave specifically, but said that the grant contributed to $6.25 million in fire recovery aid given to 3,200 affected music professionals to help rebuild studios, pay medical bills and evacuate burn sites.

Post-fire gentrification and financial speculating are new major fears. The Palisades has always been a coveted neighborhood, where working-class residents will face challenges returning to any affordable apartments lost. Altadena — home to a long-standing Black community and many blue-collar, intergenerational households — could see longtime residents forced out of their beloved neighborhood yet again, this time by economic forces.

A spokesperson for the Black LA Relief and Recovery Fund said it will use its FireAid grant to “build power among residents so they can return, reclaim and rebuild amidst political and financial threats like land grabs and gentrification.”

The Pacific Coast Highway near Big Rock Beach in Malibu, Calif., on July 8.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

FireAid moved heaven and earth to produce a benefit concert on par with the Concert For Bangladesh and Live Aid. Yet that $100 million is just a sliver of the billions in damage inflicted on Altadena and the Palisades. (Applications for the final round of small nonprofit grants are still open).

Reale and other FireAid organizers admit that the scale of aid needed is staggering, universally painful yet fraught with class and racial stratification. The FireAid concert made a profound impact for the groups serving survivors on the ground. It’s also nowhere near enough to meet the need, and never could be.

“At the beginning, we were just worried about basic necessities. Then the reality set in of ‘I have no home, I can’t go back,’” Hillsides’ Roth said. “The need we’re seeing now is helping people process that, and get a path to move forward.”